Early Days in Dan yr Ogof, and the Beginnings of OFD and SWCC

by Peter I. W. Harvey contents

At Easter 1946 the Welsh branch of the MES had organised a meet to which

everyone was invited, centred on the Gwyn Arms. The plan for the

holiday was an exploration of Dan yr Ogof led by Gerard Platten, while

the cave divers were to make an effort to pass the sump in the rising

known as Ffynnon Ddu, or the Black Spring, on the east side of the valley

lower down the river Tawe past Craig-y-Nos Castle. In the evenings

there were going to be meetings to discuss the future of the Welsh branch

of the Mendip Exploration society, or perhaps the formation of a new Welsh

caving club. A large number of cavers had arrived in the Swansea Valley

to take part in this, the first meet since the end of the war. These

were mostly from the various clubs from Somerset. Of the local members

present, Arthur Hill and Ted Mason were the main instigators. Their

letter in the British Caver (Vol 14 p.72) recommended the formation

of a new club, possibly called the ‘South Wales Cave Club’.

This was later backed up by a letter written by Don Lumbard. (Vol 14 p.

87).

Permission

had been gained from the owners of Dan yr Ogof for Gerard Platten to lead

parties across the lakes of Dan yr Ogof to the extensive dry series of

huge chambers beyond. Dan yr Ogof was first explored by the Morgan

brothers of Abercrave and their friends as early as 1912, when they managed

to reach the shore of the third lake. On a further expedition they

returned with a coracle and the party of four crossed this lake, referred

to as the ‘Coracle Pool’. They climbed the cataract

and saw the watery passage disappearing into the distance before they

turned back. Mr. E. E. Roberts, a well known Yorkshire climber and

potholer was visiting the Swansea Valley in May 1937 and was asked by

the Morgan brothers to complete the exploration. Mr. Roberts writes

in the Yorkshire Ramblers Journal (vol.VII No.23): Permission

had been gained from the owners of Dan yr Ogof for Gerard Platten to lead

parties across the lakes of Dan yr Ogof to the extensive dry series of

huge chambers beyond. Dan yr Ogof was first explored by the Morgan

brothers of Abercrave and their friends as early as 1912, when they managed

to reach the shore of the third lake. On a further expedition they

returned with a coracle and the party of four crossed this lake, referred

to as the ‘Coracle Pool’. They climbed the cataract

and saw the watery passage disappearing into the distance before they

turned back. Mr. E. E. Roberts, a well known Yorkshire climber and

potholer was visiting the Swansea Valley in May 1937 and was asked by

the Morgan brothers to complete the exploration. Mr. Roberts writes

in the Yorkshire Ramblers Journal (vol.VII No.23):

Mr Jeffrey Morgan came

up and told us the tale of 1912, how he and his brothers had found a dry

cave above the river cave (which can only be followed a painful 80 yards)

and explored it up to a great pool. A coracle had been bought and

in it Mr. T. A. Morgan had voyaged 40yds across the pool and 20 yds up

a tunnel, landing near the foot of a waterfall. Pulling the coracle

back with string, three others had followed, and after the leader had

climbed the cataract and seen a watery tunnel beyond they had retreated.

The Morgan brothers in their 1912 exploration saw beyond the cataract

above the third lake but did not go any further. To get this far,

considering they had no experience of caving must be regarded as quite

a feat. It was on a ledge in the Cauldron that they left a bottle

with their names to commemorate this expedition. It reads ‘June

1912. Jeffrey Morgan, Tommy Morgan, Edwin Morgan and Morgan Williams (Gamekeeper)’.

E. E. Roberts first entered the cave on the 23rd of May 1937 accompanied

by Platten, Nelstrop and Gowing. They took with them a rubber boat,

christened ‘Red Cymru’. There had been quite a lot of

rain during the week and and when they reached the third lake there was

a narrow sandy beach between that and the second lake. The water

was therefore quite high but not out of the question. The third

lake is an intimidating place, especially with scum from a recent flood

still on the walls and roof. They all used the boat to paddle round

the lake and into the tunnel but did not make any attempt to approach

the cascade. The flow out of the tunnel was quite strong so further

exploration was not attempted that day. back

to the top

Two days later, on the 25th. May, Ashwell Morgan, Ashford Price [senior]

and David Price of the Gwyn Arms, with three others, also visited the

cave. Later in the summer, T. A. Morgan, Ashford Price and Miss

Coote crossed the Third Lake using a wood and canvas boat. They

climbed the cascade and reached the lip of a fourth lake.

It was in September 1937 that the major exploration took place.

There appear to have been a large number of people present in the Swansea

Valley at that time and taking part in the exploration. These included,

once again, the Morgan brothers, Miss Coote, E. E. Roberts, Ashford Price

and many cavers from Mendip. The average size of exploration parties

seems to have been about fifteen. Gerard Platten appears by now

to be in charge of the exploration and sets out the early history of Dan

yr Ogof in Volume II of the British Caver:

Situated below Dan y Ogof

Farm, Craig y Nos, Breconshire, the Afon Llynfell issues from the cavern,

its entrance being at the foot of a precipitous carboniferous limestone

crag, joining the River Tawe lower down the valley. In 1912, the

three Morgan brothers of Abercrave found the entrance to a series of caverns

above the river in the cave and they penetrated to a distance of about

2090 ft. Realising its beauties, they wisely blocked up the entrance.

This year, (1937), they were able to purchase the land surrounding the

cavern. One project is the boring of a tunnel above the river entrance

and the lighting of part of the cave to enable the public to see the wonders

within. It will certainly rival Cheddar Show caves. Mr. Morgan

appeals to the public not to try and enter until this has been done.

A steel door has been erected to prevent anyone entering.

In May 1937, the Yorkshire

Ramblers Club were invited by Mr Morgan to explore the cavern. Under the

leadership of E. E. Roberts, a team went in but were beaten by the height

of the water on the lakes, which back-flood during high water. From

then onwards, all ‘club’ exploration trips were led by myself

[Platten] supported by fine teams of women and men drawn from the MES,

WCC, MNRC and the BSA. On Sept. 19th, fifteen cavers made a major

attack and succeeded in passing the third lake, climbing a series of waterfalls,

wading deep pools and, with a small boat which we carried with us,

crossed the fourth lake reaching a remarkable series of dry, sandy, immense

caverns, winding passages and everywhere brilliant with stalactite and

stalagmite formations great and small. 1000 ft was added and the

1937 cave became a reality. Again on the 20th another 2070 ft was

found and still the cave went on, but we had to retreat for fear of the

lakes filling up and cutting us off.

Another team explored

still further on Oct 13th, finding three new vast chambers, one of which

contained thousands of ‘straw’ stalactites, many over 7 ft

long. Several high avens were examined and a great many photographs

were taken.

With the water level at

its lowest for many years, a team of fifteen went in on Oct 23rd and succeeded

in adding about 400ft to the furthest extent of the cave. From this

date onwards it rained most days and the flood waters rose higher daily,

preventing all trips beyond the third lake. Daily, until the end

of the month, the 1912 cave was re-examined and two new grottoes were

discovered.

The total distance in

has reached the astounding figure of well over 1800 yards and yet the

end is not in sight. The full trip takes about eight hours.

Great thanks are due to

Messrs J. and T. A. Morgan, who gave us every assistance in their power

and who at each weekend trip supplied the hungry cavers with food and

refreshment at our base, the Gwyn Arms, where we slept and were catered

for excellently.

Another account appears in the Journal of the BSA (vol.2 No.3) by Don

Lumbard, who actually took part in the first crossing of the third and

fourth lakes. On this occasion Platten volunteered to stay at the

lakes and watch the level of the water in case it rose while they were

inside the cave. He had a revolver with which to warn the others

of any increase in level; it is also reported that he had a bottle of

rum to keep him warm. When the others emerged from the dry series

beyond the lakes, apparently Platten was asleep and the bottle of rum

was empty. Don’s account is as follows:

To those who are accustomed

to the twists and turns of the flesh-removing Mendip caves, the prospect

of exploring an extensive cave in Wales, where it is said that a carriage

could be driven through the passages and where underground lakes had to

be passed by using inflated rubber boats, was indeed inviting. There

was also talk of a mighty whirlpool which made one imagine that an arm

waving a sword might suddenly appear as if in challenge. However,

even when the usual exaggeration of the enthusiastic caver was allowed

for, the possibilities of an enjoyable trip were great. To our surprise

the statements were substantially true, for Dan-yr-Ogof has now been explored

for over a mile, there two lakes to be crossed by boats and a whirlpool

is formed when the water is very low.

Mr Ashwell Morgan, one

of the owners of the cave, has already written of an exploration in 1912

when a party penetrated half a mile, and it is now proposed to give some

description of the new half mile or so discovered this year.

Mr G. Platten undertook

to organise and lead the explorations. The first main onslaught

was made on 16th September (1937) when our party was G. Platten, V. Wigmore,

C. W. Harris, F. Brown, I. A. Morgan and some others.

We entered the cave at

8am on the Sunday and leisurely went through the 1912 cave until we were

all assembled on the strip of sand separating the 2nd and 3rd lakes, ready

to begin the serious part of the exploration. Accordingly, two of

us were despatched in the canvas boat to see whether the journey up the

falls could be accomplished, and report on the possibilities. A

line was fixed to the boat and signals were agreed.

In the distance we could

hear the roar of water and as we paddled slowly on with our candles giving

all too little light, the current became stronger until, when our sense

of awe had reached its maximum, we saw the falls or rapids as they really

are. The spell was broken and our immediate desire was to leave

the boat as soon as possible and get onto something firm. We therefore

moored the boat and negotiated the falls by climbing around the edge of

the passage for a distance of about 20ft until we came to a still pool

which disappeared to the right. We clambered round the right hand

side for a few yards but found that, if we were to continue, we should

get fairly wet, which seemed unnecessary as there was a rubber boat with

the main party. So back we went with the news that the falls could

easily be passed but that the other boat would be needed.

The exploration of the

1937 cave then began with ‘Digger Harris’ as leader, Gerard

Platten generously staying behind to be sure of communication. On

this particular trip he carried a revolver which was to warn us if the

water suddenly rose. It must be said that on these trips there was

a very fine team spirit which was a little return for the self sacrifice

of Platten who laboured endlessly to make the show a success. back

to the top

There has never

been any repetition of the feelings experienced on that first crossing

of the Third Lake. It was now routine work with a candle light welcoming

one at the end, and so on to the still pool which was now circumvented

by wading round the left hand side until some more rapids, which came

from the Fourth Lake, were reached. At a rough guess the lake is

about 15yds across. On the left side, Bill Weaver fell out of the

rubber boat into deep water while investigating water flowing into the

lake. There has never

been any repetition of the feelings experienced on that first crossing

of the Third Lake. It was now routine work with a candle light welcoming

one at the end, and so on to the still pool which was now circumvented

by wading round the left hand side until some more rapids, which came

from the Fourth Lake, were reached. At a rough guess the lake is

about 15yds across. On the left side, Bill Weaver fell out of the

rubber boat into deep water while investigating water flowing into the

lake.

The rest of Lumbard’s article goes on to describe the cave beyond

the lakes, which remained much the same until the major break-through

in 1966. Some modern cave explorers have been known to belittle

their forebears for lack of push and courage, but it must be remembered

that in those days they had no great experience or knowledge of caves

to draw on. Attempting to cross the Third Lake in a coracle using

a poor light must have been an awe-inspiring experience especially as

the sound of the cataract round the corner could have been the river pouring

down a hole in the floor ready to engulf both coracle and passenger, and

so it was not until the late nineteen thirties that the lake was finally

crossed.

The entrance during the early years was in via the river exit and a climb

up into what is now the show cave. When the show cave was opened

for a short while in 1939, a new entrance had been blasted at a higher

level, making an easy walk in. Also, a water turbine was installed

outside the cave to generate electricity for the cave lighting.

The onset of the Second World War brought all this to a halt. During

the war the cave was used as a safe storage area by one of the Ministries

and was therefore not available for exploration. After the war,

permission was again obtained to explore the cave, which led to the Easter

meet of 1946.

The main excitement in Dan yr Ogof was, of course, the crossing of the

series of four large lakes joined by cataracts which were reached after

the end of the showcave. Few people had ever seen these lakes and

this fact alone increased the awe in which they were held. The first

two lakes were quite shallow, being not more than about two feet deep.

Splashing through these tended to give newcomers the impression that all

the stories they were told were exaggerated. However on reaching

the edge of the third lake, with the thunder of the cataract round the

corner, it was obvious that those stories were right. In low water

the third lake was usually over waist deep. The fourth lake is about

the same depth, but by now everyone is pretty wet anyway.

In flood conditions the lakes are impassable. Under these conditions,

the noise from the cataracts is muffled. The first two lakes would

now be quite deep and would both be joined with the Third Lake, which

would be up to the roof of the passage blocking off the tunnel to the

cataracts. If you were unlucky to be caught on the wrong side you

would have to wait until the level of the water subsided. Nowadays

there is a store of food and other comforts kept on the far side for emergency

use.

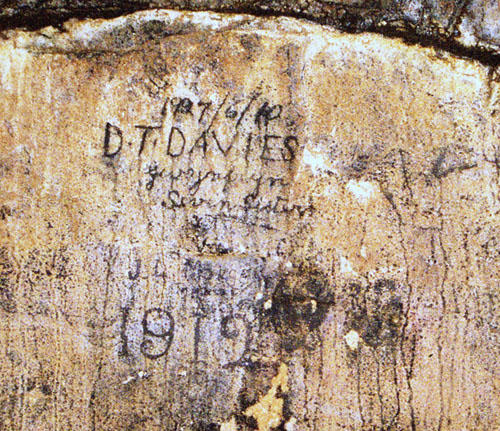

Past the lakes there are several large chambers containing fine formations,

especially straws, some over 6ft long. Beyond those is a very tight

and tortuous passage now known as the ‘Long Crawl’. This had

never been passed, although Bill Weaver and Don Lumbard had spent a lot

of time examining it before the war. At the end of one long exploration,

after climbing a 30ft aven they reached a small chamber after a crawl

along a tight passage and left their initials scratched in the mud: P.

W. and D. L. These were found a long time later in the 1980s, revealing

that they were not a long way off from getting to Dan yr Ogof II via the

‘Longer Crawl’, an even longer route through the maze of tight

passages.

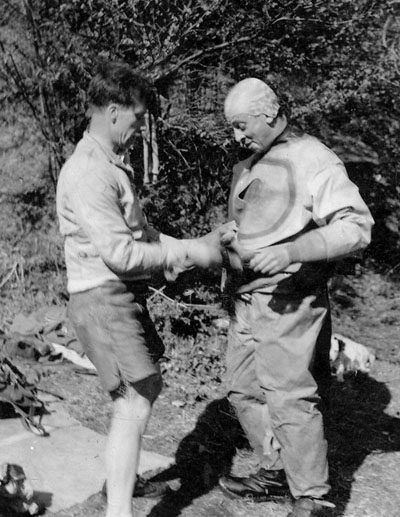

Before the days of wetsuits [or furry suits], Dan yr Ogof was a cold

cave. After wading through the lakes, which usually meant getting

soaked up to the armpits or higher, one tended to get rather cold after

spending several hours in the dry chambers on the other side in wet clothes.

As this series consisted in the main of large chambers, the caving was

not energetic enough to generate much heat. Also there was a considerable

draught in the cave which contributed to the general chill. Some

of the old hands such as Platten used to cover their bodies with about

half an inch thick of lanolin grease before putting on their caving gear.

This operation could generally be viewed on the roadside outside the Gwyn

Arms. Charles Freeman writes in the British Caver (Vol VI pp 27.)

Also a wonderful

difference can be made by greasing the body all over, when changing into

caving rags, with commercial vaseline. A handful should be taken

up and rubbed well into the skin , not just smeared on. …

Its use certainly transforms one into a hero in the eyes of those who

have scorned to annoint themselves.

I never fancied this and later on I adopted the different ruse of undressing

completely on the edge of the third lake. I waded through the lakes

naked, carrying my clothes in a rucksack on my neck, and dressed on the

other side. One is rewarded with a lovely warm feeling when dressed

again in dry clothes. I did not bother with this on the way out

as we would not be hanging about in wet clothes for long and it also ensured

that one’s caving outfit was quite clean when emerging from the

depths.

I had been looking forward for some time to the Easter Holiday (1946)

and the chance to see Dan Yr Ogof. I had heard so much from Bill

Weaver about the huge chambers beyond the lakes. that I had constructed

a special lamp to be able to see them properly. I had soldered together

twenty four cycle batteries which were to be used to drive a motorcycle

headlamp for an hour or so. This worked very well but it was bulky

and the batteries were so heavy they had to be carried in a gasmask case

which I carried on my chest.

I left my work in Bristol on my heavily loaded motorcycle on the Thursday

evening before the Easter Holiday and arrived at the Gwyn Arms at about

8:00pm. The place already sounded pretty full and as I was leaning

the bike against the wall a scruffy, hairy character came out of the pub

and said “I am the leader. Who are you?”. Although

I had never met him, I realised this was Gerard Platten. While he

was telling me all about the coming weekend, I was mesmerised by the green

snot that hung down from one of his nostrils, going up and down as he

breathed. Eventually after getting longer and longer, it caught

on his bristly moustache. This must have been the end of the cycle

for at this stage he wiped it off on his sleeve and the whole process

started again. After being briefed for the weekend I went into the

Gwyn. All my friends were there, as well as about 40 people I did

not know. Ian Nixon, John Parkes and Bill Weaver were already inside

consuming beer. The more the beer flowed, the more people I got

to know. It did not seem long before our host, David Price

called time - in those days it was 10 pm - and it was not long before

I was in the barn unconcious in my fleebag.

Next morning we were all up early. This was my second visit to

Wales and the weather was perfect. At about mid-morning everybody

assembled outside the entrance to Dan yr Ogof, 20 or 30 people in

all. The steel doors were unlocked and we were ushered in by the

leader. back

to the top

The old show cave section was relatively uninteresting, with its wiring

and concrete paths, but towards the end the dull roar of the river section

could be heard. We came to a steel fence and some steps going down

and there was the First Lake. As expected, this was a bit of an

anti-climax because it was not very deep and we all splashed through.

It was the same for Lake 2. As we stood on the edge of Lake 3 we

realised this was a different proposition. There was scum on the

water and on the walls and roof, evidence that in the recent rains the

cave had flooded up to the roof; the sound of the cataract beyond

was very loud. The lake curved round to the left so the cataract

could not be seen. Some people made use of a rubber boat and line

to cross but most, including me, waded across using the left-hand wall.

With a bit of luck with one’s footholds it was possible to cross

just less than chest deep. On crossing this lake, we were at the

cataract between the third and fourth lakes where the underground river

thunders down at an angle of about 30 degrees. At the head of the

cataract there was a section not more than 4ft deep before we came to

the lip of the Fourth Lake. This was crossed on the right hand side

and was no problem and was not much above waist deep except for the final

step, which was about the same as lake three.

After the fourth lake and a short climb into a black tube about

five feet diameter we were in the dry part of the cave. We were

in Sand Chamber and were able to look down into the final sump.

This could be reached from the Fourth Lake in very low water conditions.

These chambers were not as large as I had been expecting and my motorcycle

headlamp gave a magnificent light. The straws in Straw Chamber were

very fine. This was the last time that this light was used because

I dropped the headlamp into the cataract on the way out and was unable

to retrieve it!

Outside in the sunshine we changed into dry clothes and most of us made

our way round to the spring called Ffynnon Ddu, the resurgence on the

east side of the valley just south of Craig y Nos Castle, Madame Patti’s

old home. It was here that the divers were operating. The

stream that comes out here is much smaller than at Dan yr Ogof.

The water was assumed to come from one of two large swallets: Pwll

Byfre, about one and a half miles to the north-east, and Pant Mawr about

a mile further east. There was no real proof of this but there were

tales of dogs disappearing into Pwll Byfre and reappearing some time later

at Ffynnon Ddu with no hair on! There was another story of a load

of chaff being thrown in at the sink and coming out at the rising, but

the connection had always been only an assumption.

There was a large crowd at Ffynnon Ddu when I arrived, mostly spectators.

The divers were Graham Balcombe, Jack Shepherd and Bill Weaver.

Graham and Jack were well-known divers and had been the first to pass

Sump 1 in Swildons Hole in the Mendips. Bill was still a trainee

diver and this was to be his initiation; I was acting as his

dresser and log keeper. We had already completed several open air

training dives, in the mineries pool on Mendip and Henleaze Swimming pool

in Bristol. This was to be his first dive into a cave under the

supervision of Grahame. He was, when trained, to form the nucleus

of the Welsh section of the newly formed Cave Diving Group. As it

happened, the passage beyond the entrance [the resurgence] had collapsed

and no progress could be made into the cave. At the end of the second

day, Graham set a charge off on one of the boulders in the sump; there

was a satisfactory dull thud, the water became a bit murky and a dead

fish floated out belly-up. Anyway the spectators had had a fine

day in the sun watching the slow process of dressing and diving.

Mrs Bannister and her two daughters, living in the nearby cottage known

as the ‘Grithig’, provided the divers with cups of tea.

Now that the serious diving had come to an end, a few novice divers, including

Arthur Hill, had a dip in the resurgence pool.

During lulls in the excitement I had been looking around the area.

There had been a small amount of digging, with a view to entering the

cave which was obviously there, but this had been during the war when

the exploration of Dan yr Ogof had been suspended. Before the war,

when Dan yr Ogof was still not fully explored, there had been no spare

time to consider digging at Ffynnon Ddu. Cyril Powell, owner of

the land, with the help of the local cavers, among them Arthur Hill and

Ted Mason, had dug into a small cave with a lake which they originally

called Ffynnon Jenkin but later became known as Pant Canol, after the

little valley it was in. This cave consisted of a tight entrance

leading down to a lake, the water in which was reputed to be the coldest

in South Wales. On the other side of the lake there was a small

hole too tight for further exploration but which had a draught.

On the road above, leading to the quarries at Penwyllt and the station,

there was a cave entrance. Cyril Powell had dug this out some time

before and it was therefore known as Powell’s cave or Penwyllt Cave.

This was just a relic left when the glaciers altered the landscape during

the ice ages, but nevertheless was perhaps indicative of the larger cave

beneath. Bill Weaver in his jottings in South Wales (British Caver,vol

VI p 52,) writes:

On the Monday [Easter

Monday 1946] we took a walk up the Penwyllt Valley and called on Mr Powell

at Rhongyr-isaf Farm. He took us up to a spot on the hillside where

he had opened out a swallet, disclosing beneath the drift a cave in limestone.

Apparently his uncle used to work rottenstone here and had broken into

a large cave system which was subsequently lost. He has most certainly

re-discovered it. The stream falls into the rift and then filters

away through a mass of fault breccia. A large volume of water could

be heard in the distance.

Then he took us up and

showed us the old rottenstone workings, long since derelict. From there

we went to the quarry on the right-hand side of the road where a large

cave entrance is seen. Mr. Powell discovered this when working the

limestone and has since opened out an upper entrance.

And so on to Ffynnon Ddu

(the Black Well) behind Craig y nos Castle. The possibilities here

are enormous, diving is ruled out for obvious reasons, but a few days

digging should give the required results. This outfall is most certainly

the result of the Pwll Byfre sink some miles away towards Pant Mawr.

(This connection has already been established with chaff. Ed.).

Here again is a swallet with enormous potential.

Ian Nixon was with me and we decided that the area was much more promising

than the Bath Swallet at the UBSS hut on Mendip, so we spent some time

looking round for a likely place to make an entry into the cave that must

be there. We made plans to spend several weekends during the summer

looking for the cave.

The main activities in the evenings [of the Easter holiday 1946] were

eating, drinking beer and attending meetings. The important meeting

of the holiday took place on Saturday 20th of April This took place in

the Gwyn Arms, in what was called the Coachhouse, chaired by Brig. E.

A. Glennie [who in later years was to be SWCC President]. A lot

of people spent a lot of time talking but the net result was that in the

first meeting the MES was disbanded. In the following meeting a

new Welsh club was formed which was to be called ‘The South Wales

Caving Club’ or, in Welsh, ‘Clwb Ogofeydd Deheudir Cymru’.

I was rather confused when I noticed that those who did the most talking

at the meeting never joined the new club. The annual subscription

was set at ten shillings, with an entrance fee of five shillings.

Arthur Hill was the first secretary, Ted Mason was elected chairman and

Charles Freeman was the treasurer. The meeting had decided that

it would be appropriate to start the new era of caving after the war with

a truly Welsh club. At another meeting which took place, The

Cave Association of Wales was formed. Ted Mason was the secretary.

This was supposed to be a body to which all the clubs interested in the

South Wales area could affiliate. However, it never really caught

on and finally faded away. Later, when national bodies were all

the rage, the Cambrian Caving Council was formed, doing much the same

job, whatever that was, as the original Cave Association of Wales.

The Easter weekend had to come to an end and it was necessary to pack-up

return to work in Bristol. It was hard tearing myself away from

this interesting valley but I intended to return as often as the petrol

ration would allow. Petrol rationing continued until 1954, including

a period with nothing at all, and caving in Wales, for me, depended on

the ration and whatever extra petrol coupons I could acquire. Several

times I travelled by train to Neath and changed for Penwyllt station,

on the Neath to Brecon railway, which was still running in those days,

and continuing to the Gwyn by taxi. Another popular route was to use the

train to Swansea and travel on the bus up the Swansea Valley to the Gwyn

Arms. Public transport after the war, by modern standards, was very

good. The main difficulty was the mountain of gear which had to

be carried for a weekend’s caving; the new club did not as yet have

a base in the area so everything for the weekend had to be carried.

Edited by Jem Rowland, back

to the top

March 2009

|