Mendip, Sinc y Giedd, Pwll Dwfn etc., 1947-48

by Peter I. W. Harvey contents

After the excitement of the discovery of Ogof

Ffynnon Ddu, life gradually drifted back to normal. Petrol rationing

was still in force, which meant that excursions to Wales only took place

every four or five weeks. The return journey to Mendip, from Bristol,

could be done with less than a gallon of petrol on my motorcycle but a

weekend in Wales needed at least four gallons. Over a gallon could

be saved by travelling with the motorcycle on the train through the Severn

Tunnel, from Pilning to Severn Tunnel Junction. As the ration was

only about four or five gallons a month, a lot of my time was spent on

the Mendips. I had joined the WCC several years previously and this

became my main club whilst on Mendip.

The WCC at this time was run by its secretary, Frank Frost. With

Frank you were either in or out. I was usually out! I was

talking to a new member once and he said to me “I am not supposed

to talk to you, Frank said you were a bad influence.” One

year, I proposed somebody else for the job of secretary and Luke Devenish

seconded the proposal. By return of post I received a letter from

the chairman telling me to withdraw my proposal as Frank wished to be

secretary again. Luke also had a letter and, unfortunately, he chickened

out! This did, at least, start the appointment of an assistant secretary,

which made the running of the club a bit more open. I believe the

Wessex has now returned to the ranks of the democratic clubs! One

verse of a Wessex cave club song reads:

Frank Frost, he was

our leader, our leader was Frank Frost

And though he was a bastard, without him we were lost.

His wisdom was eternal, he was our guiding light,

He filled the Wessex journal with malice, hate and spite.

Back in Wales, now that the

exploration of Ogof Ffynnon Ddu was slowing down, Ian [Nixon] and

I were turning our interest elsewhere. Behind Dan yr Ogof, about

two miles to the north-west, was a large swallet taking a stream which,

in times of flood, was the size of a small river. This swallet was

called Sinc y Giedd and was about a mile beyond the one the Dolphin Gang

had been digging since 1938, called Waun Fignen Felen after the peat bog

which it drained. It was believed that both these streams resurged

at Dan yr Ogof but there was no evidence of any water testing having

been carried out. Bill Weaver told me that he had examined this

swallet before the war and had managed to get underground where the water

sank and reached quite a large chamber. As he was alone he had not

prospected any further. For all his knowledge of the area,

I always regarded Bill as great story teller.

We obtained permission to dig on the mountain from Mr. Ward, Lord Tredegar's

agent. This took rather longer than we expected because Mr. Ward

got the idea we wanted to open a show cave two miles from the nearest

road! Ian and I decided to start digging this sink at Easter 1947

by camping at the site in the Giedd Valley. We had visited Sinc

y Giedd several times during the winter of 1946/47 and had examined a

number of small holes in the vicinity of the sink but we never managed

to find the hole Bill had found. We uncovered one small bedding

plane which looked quite promising as it obviously got bigger inside.

It was much too small for Ian or me, but we had two girls with us, Brenda

and Phyllis. Brenda managed to squeeze through the nine inch space

but Phyllis, who was complaining that her chest was too big, got no sympathy

and was told, “Stuff them under your armpits and get in there”.

Unfortunately there was only 100ft of bedding plane and nothing else,

so we decided to dig at the main sink where Bill claimed he had some success.

I tried to visit the sink once more before Easter with a rucksack full

of tinned food, to sustain us during the intended camp, but the visibility

was so bad in the pouring rain that I stashed the food in a sink hole

to be picked up later and returned to the Tawe Valley. Food was

always fairly difficult to obtain as a lot of it was still rationed for

a number of years after the war, though vegetables were always fairly

plentiful. The usual procedure was to club together and make a stew

with whatever everyone had. I can remember many fine stews, but

it was often a good thing not to enquire too deeply into the ingredients.

I remember once when I had been lucky in obtaining a pound of sausages.

The others were cooking the potatoes and beans so I was on my own frying

the sausages. I put them in the frypan with some fat and after a

minute or so it was obvious that there were little things inside trying

to get out through the skin, away from the heat. The topside of

the sausages looked quite hairy! The others had not noticed anything

so I quickly rolled them over and, after cooking them well, served them

up. There were no complaints or any ill effects. Whatever

the age of the sausages there were certainly some fresh ingredients in

them.

Easter 1947 arrived, and I managed to get a lift to Wales in someone’s

car. The weather that year had been awful, with sleet, heavy snow

and high winds, and we had planned to camp at Sink y Giedd, high on the

mountain. On the Saturday morning we rose early. All the party

had arrived at the Gwyn and we were all at Sinc y Giedd before midday.

It was decided that because of the dreadful weather Kay Dixon and I would

camp at the sink while Ian and the rest would stay in the valley and come

up daily. The dig was started at the main sink. We managed to dig

down about 6ft that day, the day workers leaving about 6pm and the campers

retiring to a good night’s sleep at about 9pm. We were camping

beside the stream which flowed into the swallet, which is at an altitude

of about 1400ft. During the night, the noise of the stream ceased,

indicating that the temperature was well below zero. We rose at

6 am next morning and, after a good breakfast, carried on downwards.

Eventually, after wrestling with a large boulder in the bottom of the

hole, we drilled it and with a small charge the bits dropped down the

hole. We had broken the shafts on both our sledgehammers, which

had been at the sink since the previous November. At this point

it started to rain again and Mike Gummer arrived from the valley.

The hole was now 10ft deep, leading to two parallel passages each about

3ft high and joined by a bedding plane. From the far passage there

was another 10ft drop into another passage going north and south.

Ian, Brenda and Liz had arrived by now and the rain was coming down in

real Welsh style. We decided , as the river would soon be flowing

down our dig, we would retire to the valley and the Gwyn Arms. Next

day, in the rain, we removed all our equipment, hoping to return for the

Whitsun holiday when we might expect some better weather. The chances

of getting into a cave of some length now looked very promising but we

were high up on the open mountain, a long way from the road and the weather

was too much for us.

It was on our return that we learned that Dolphin, Lander and Colin Low, collectively known, with Norman Paddock, as the ‘Dolphin

Gang’ had found a promising hole in the Dan yr Ogof valley which

they described as “very dangerous”. They had been sheltering

from the wind and rain in a small depression to consume a snack when they

heard the sound of running water beneath them. It was not long before

they had removed enough soil and boulders to enter a sloping passage with

the stream running along the floor and which after about 20 ft dropped

down a pitch. They returned quickly to the Gwyn for some rope ladder.

They returned again later for all the available ladder. They had

descended one short pitch of about 20ft but there was another one immediately

beyond it. Unfortunately, at the bottom of the second pitch which

was about 55 ft, they found a third pitch for which there was no more

tackle. It was decided to acquire more ladder and have another attempt

at a later date. back

to the top

Immediately after the war, tackle consisted of ladders made from rope

with wooden rungs, which would have been made at least seven to ten years

previously and stored in unknown conditions. It was therefore fairly

unreliable. I was now making new rope ladder but up until then

had not finished very much. Later on, I managed to supply the needs

of both the Wessex and the South Wales Caving Club. I always enjoyed

climbing rope ladders, compared with the later wire and aluminium rung

variety. Rope ladders were, of course, much heavier and bulkier

but were slightly elastic so that, when climbing, one could get a rhythm

going with the bounce and this was a help in climbing.

On Mendip, meanwhile, I had been intrigued by a deep depression about

two miles north-east of the Hunter’s Lodge. Bill Weaver was

also interested, and we decided to have a go at digging it, perhaps with

the help of the Dolphin Gang. First of all we had to find out who

owned the field and Bill agreed that this would be his job. Looking

through the old mining maps, I saw that the area this depression was in

was called Cuckoo Cleeves, so we used this name when referring to our

proposed dig. Bill was lucky in locating the owner and, after getting

permission to dig, we decided to start at Whitsun helped by Leslie Millward.

I was to join them on the last day of the holiday when I returned from

Wales.

Back in Wales, the Dolphin Gang had assembled some more ladder and invited

Bill Weaver, John Parkes and myself to join them on 27th April for the

exploration of their new pot, which they had named Pwll Dwfn, or ‘Deep

Pot’ in English. I was able to help them with a few lengths

of my own rope ladder. We descended four pitches, the last

being 80ft, and a short climb down to the head of another pitch which

was at least 60ft deep. Even using the ladder on the third

pitch again, we still did not have enough to reach the bottom. The

total ladder needed was about 260 ft. There was nothing for it but to

retreat and arrange another date, which was July 6th. The place

did not seem all that dangerous. The First two pitches were a bit

loose and seemed to have large loose rocks in the wall that were sufficiently

keyed in so that they could not fall out. The rest of the cave appeared

pretty solid. There was very little horizontal passage, probably less

than 50ft in total, as one pitch was followed closely by the next.

It was now Whitsun and Ian, Mike Gummer and I went over to Wales to see

how far we could get into Sinc y Giedd. We were lucky with the weather

and there was no water going in at our dig. It had not been filled

by flood debris and we were able to reach the furthest passage we had

seen at Easter. To the north it got too small after about 20ft,

but to the south it curled round and down into quite a large chamber.

This was could have been the same chamber that Bill Weaver said he entered

before the war. From this, there was a round passage about 3ft in

diameter leading off in a westerly direction, for the first time in solid

rock. After about 35ft, it cut into the top of an aven about 40ft

above the floor below. Just below our opening was a band of chert,

so we could stand one foot on either side looking down as the aven

opened out below us. Of course, we had no ladder with us so we decided

to call it a day and return in August, when we were intending to spend

a week in the area. Sink y Giedd was certainly still looking very

promising. The rock we were now in was solid. Until we entered

the large chamber, the cave appeared to be large rocks, the size of small

houses, just resting on each other, which suggested to me that it was

a very young swallet where little collapse had as yet taken place.

Looking at the surroundings, it could be seen that the stream had carried

on down the valley before the swallet was formed. In the cave there

were no formations of any kind and everywhere was waterwashed black rock

with flood debris lodged everywhere up to the ceiling. It was obvious

that in time of flood the whole place was filled with water - not a place

to be caught in during a cloudburst!

I left Wales with one day of the holiday remaining. This was reserved

for Mendip, to see how Bill and Leslie had fared with the dig at Cuckoo

Cleeves. When I arrived they were not there but it was obvious that

they had done magnificently. They had dug a shaft about 20ft deep

in glacial mud and boulders and there was actually a black hole at the

bottom, but I could see that if the sides of the shaft were not supported

pretty soon, everything would be lost. I tracked them down and found

them in the Hunter’s Lodge nearby, where arrangements were made

for obtaining timber and shuttering. The next Saturday, Bill and

I were up early and by midday had shuttered most of the shaft, although

a bit had fallen in. Leslie arrived after midday and by about 10pm

we had made an entrance. As it was now pretty late, we decided to

explore it on the following Wednesday evening. back

to the top

The following Wednesday saw the three of us at the entrance with 120ft

of ladder and associated tackle. One of Sod’s laws is

that if you need ladder you won’t have it with you and if you don’t

need ladder there will plenty available. At the bottom of the shaft,

after going through a small chamber, we were in a short descending passage

and then after passing a swinging block of stone, which seemed hinged

rather like a door, there was a short drop on which we used a handline.

At this point we were in a sloping chamber, at the bottom of which a narrow

passage led off in a south-easterly direction for about 200ft then changing

direction to the south-west, finishing in a bedding plane chamber sloping

at about 45 degrees. After about 10ft this chamber closed down to

a crack about six inches wide and much too narrow to get through.

It was while we were sitting down at the end of the cave considering the

possibilities and all was quiet that a boulder moved below us and rumbled

down a slope. It was a very eerie sound and, not being sure what

to make of it, we all moved out of the cave. It could possibly have

been a boulder at the entrance, which of course had recently been disturbed

by our digging activities. I can’t remember if we had told

anyone where we were that evening!

The rift passages down to the terminal chamber were interesting in that

the rock contained numerous fossils and was worn away to leave the fossils

sticking out proud of the rock. I imagine that today, after the

passing of many cavers, a lot of the walls have been worn smooth.

July arrived and we were all back in Wales for the final exploration

of Pwll Dwfn. The same party as before had assembled in the Swansea

Valley with at least 350ft of rope ladder. It was arranged that

our party would ladder the cave on the Saturday and, on the Sunday, a

group of SWCC members would descend the pot and remove the tackle.

The 350ft of ladder plus the associated tethers and lifelines was a formidable

load for six of us to carry up the mountain so Paul had organised a horse

to help us, complete with a driver. This saved us carrying some

of the tackle, but took considerably longer because none of us seemed

capable of loading the cargo on the horse’s back reliably.

We had to reload the horse a couple of times when, instead of being on

its back, the load slipped and hung from its belly, thus making it difficult

for the poor animal to work its legs properly.

Of the trip itself, there is little to record. We were expecting

to drop into a vast system of horizontal passages behind the known parts

of Dan yr Ogof, but caving is never like that. There seems to be

some rule that allows only a bit at a time. We quickly descended

the first four pitches and, with great expectations, threw 60ft of ladder

down the fifth pitch. Paul and another climbed down but there was

no way on, only a miserable pool of water in the floor. This was

a big disappointment to us all, but there was the consolation that Pwll

Dwfn was like nothing else in Wales. It was more like the potholes

found in Yorkshire. Much later on, on January 24th 1964, Bill Clark

and Charles George organised a dive in this terminal pool but were disappointed

to find no way on underwater.

August arrived and Ian and I were back in the Swansea Valley with our

attention now again on Sinc y Giedd, ready to explore the miles of passage

that lay below the pitch. Mike Gummer and Kay Dixon had also arrived.

The SWCC had now been given the use of a cottage by Jeffrey Morgan, for

use as a headquarters, situated near the main road on the banks of the

Llynfell - the river which flows out of Dan yr Ogof. [The cottage

was known as 'Penbont' and has since been demolished as a result of road

realignment.] This was very convenient, being both close to the

caves and the Gwyn Arms. We had fitted it up with about a dozen

bunks and facilities for cooking. The girls were still accommodated

at the Gwyn as Arthur Hill, the club secretary, thought that the local

people in the valley would disapprove if they slept in the same building

as the men. This was quite an inconvenience as we usually rose in

the morning about 5am and this meant instead of just kicking them out

of their bunks, somebody had to run to the Gwyn, a half a mile away, to

throw stones at their window in order to get them up for breakfast.

It seems a very early start in the morning after the night before but

we could not afford to come to Wales very often because of the petrol

situation. Although we always tried to drink the Gwyn dry every

evening, it was only the wartime watery brew, which did not seem to do

the damage that more modern beers seem to manage.

When we arrived at Sinc y Giedd, the weather was fine but there was too

much water going down for any exploration to take place. We left

the tackle and went for a walk to look at the other sinks in the area.

There was one taking a lot of water about 100yds further up the Giedd

and, all the way up the Giedd until it reached the Old Red Sandstone,

there were also further small sinks. South of the main sink

there was a small peat bog which was the head of another small stream

also named the Giedd on the map. It seems that in the past both

streams were one until, as it flowed over the limestone, the water was

gradually captured by the waters flowing underground. We also examined

a swallet we had not seen before to the north of Sink y Giedd called Twyn

Tal Ddraenen. We pulled a few boulders out and noted it down for

attention later on.

We returned to our sink after midday and found that there was much less

water going down. We went underground and laddered the pitch which

we had looked down last time - about 45ft of nice easy climbing.

At the bottom, the rift went north and south. There was not much

to the north, as the passage gradually closed down, but to the south there

was a high passage which closed down to a bedding plane to the left.

This opened out into a number of walking passages but all of these became

too tight after a while. As the prospects of getting into the Dan

yr Ogof system were now looking rather slim, we decided that it would

be best to look for somewhere else to dig. At the bottom of Sinc

y Giedd we were something like 100ft underground. The rock was black

waterwashed limestone with flood debris in all the cracks, just as we

had found in the entrance passages. This gave me the impression

that there would be no easy route into the main Dan yr Ogof system.

Reluctantly, we called it a day, removed our tackle and returned to the

valley. On emerging from the cave we met Don Lumbard out walking

with some friends, who helped carry some of our tackle. To crown

the day, we found that we had succeeded in drinking the Gwyn Arms dry

during the previous evening. This was not an uncommon occurrence

in the years during and after the war. Luckily the Tafarn y Garreg,

a few hundred yards up the road, was open and had beer!

The rest of this holiday was spent in trying to dig through the boulder

choke in Ogof Ffynnon Ddu. We dug in the floor on the right hand

side and did manage to reach a small passage in solid rock but it did

not look very exciting. In fact, it was so small only Peggy Hardwidge

could get into the first six feet or so. Peggy was very useful being

so small, because we could push her into any small hole we could not manage

ourselves.

One evening after the Gwyn had shut, I went with Peter Densham to the

rising across the road from Craig y Nos Castle, now used as a TB hospital.

This was known as the Hospital Water Cave. Up until now, nobody

had been in because it was thought that the hospital authorities might

refuse permission but, as they only used the water during droughts, a

very rare occurrence in Wales, we decided to have a little look.

There was a small system totalling about 600ft ending in a sump.

I remember in one place there was a horrendous looking boulder, which

did not look supported, that we had to climb over. Many people have

visited the cave since then and this boulder is still there so I suppose

it must be firmly in place. The sump has been dived by Martin Farr,

Mike Ware, and others but they have been unable to break through into

any worthwhile passages. Craig y Nos Castle was built by the Powells,

local industrialists, and was later the home Adelina Patti, the Edwardian

opera soprano. She had built into it a very pretty little opera

theatre, which is well worth a visit. She also had a private waiting

room at Penwyllt station. Madame Patti was a friend of Edward

the Caresser (Edward VII) and it is said that when he arrived for

a visit, her husband, Baron Cederstrom, retired to the hunting lodge (Ty

Mawr) at the top of Penwyllt hill near the station.

Our week in Wales came to an end and, with it, the end of a very busy

twelve months, with the opening of Ogof Ffynnon Ddu, exploration of Pwll

Dwfn, Downey's Cave, the Hospital Water Cave and a small part of Sinc

y Giedd and then the opening of Cuckoo Cleeves on Mendip. It seemed

that, in October, when the petrol ration for private use was stopped altogether,

a brake was being put on our activities. It meant that we could

not go to Wales so often and when we did it was usually by public

transport.

Towards the end of 1947, I decided to prove the connection between the

swallet at Pwll Byfre and the river in Ogof Ffynnon Ddu. On the

25th October 1947 I put 6oz. of fluorescein in the stream at Pwll Byfre.

This dye is a red powder in the bottle, stains ones hands yellow, and

yet turns the water a brilliant green in the sunlight. It was Saturday

midday when we dyed the stream. We watched at Ffynnon Ddu all Sunday

but nothing came through. It was not until midday on Monday that

Mrs. Bannister at y Grithig cottage saw that the spring had turned green.

The dye had taken approximately two days to travel the mile and a bit

underground. Soon afterwards, in March 1948, we introduced 35oz

of fluorescein into Sinc y Giedd. About 50 hours later it was seen

in the Llynfell, flowing out of Dan yr Ogof, taking about a day to clear.

We had now located the source of water of both the main risings in the

Swansea Valley. It was interesting that the Dan yr Ogof catchment

area went as far west as Sinc y Giedd; many people had assumed that

the water here went to Ffrwd Las, a rising in the Twrch Valley, a mile

or so further further west. back

to the top

My main interests in caving were now centred on the Swansea Valley and,

in particular, on Ogof Ffynnon Ddu, which had the potential of becoming

the largest and deepest cave in Britain. This did not mean that

I only caved in Wales. I was involved in several digs on Mendip.

With Leslie and Phyllis Millward we dug down 25ft in both the depressions

in the field adjacent to the Hunter’s Lodge. One of these

we filled in, the other we handed over to Oliver Wells, who carried on

with it and entered a pothole with a 70ft pitch. I had a theory

that most successful digs entered a cave before 25ft. There are

several examples of mammoth digs which tended to turn into someone's life's

work. I think I was unlucky with the Hunter’s Hole.

Looking at it now, the entrance is nowhere near 25ft. deep. We must

have been digging down beside open space! After that, we spent a

while digging at Manor Farm Swallet but were defeated by the regular floods

filling in the dig. Another dig we attempted was on the farm about

a mile south of Lamb Lair. The farmer gave us permission to dig

an interesting looking depression on his land but it was on condition

that we did not do any work on Sunday. Cave digging requires all-out

effort and in the end we lost interest.

We

also found time and petrol to visit Derbyshire and the Yorkshire Dales.

I never seemed to do very much when I went to Derbyshire. We visited

a few small caves and went down a few mineshafts, but I always had the

impression that I was on a social outing. Yorkshire, on the other

hand, was quite different. After the first day I was always aching

all over. Living in the south I was not brought up to climb ladders

all day or carry so much rope ladder around inside pots. The weather

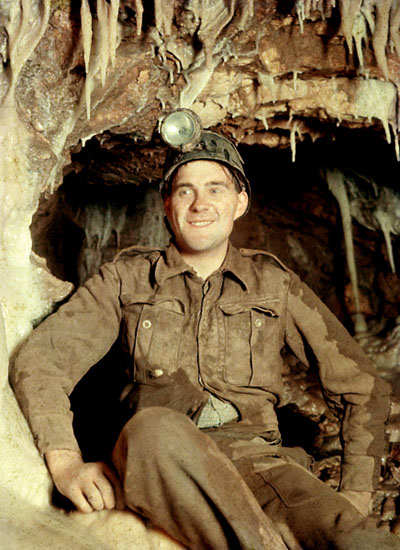

never seemed to be very kind to us and my old Home Guard uniform (pictured

left) and old sweaters used to soak up enormous quantities of water which

I had to carry around with me and up and down wet pitches. After

one hard day, it seemed I was expected to do the same again next day.

I was always pleased when the weekend was over but the strange thing about

caving is that, in retrospect, I always realized that I had enjoyed the

experience. We

also found time and petrol to visit Derbyshire and the Yorkshire Dales.

I never seemed to do very much when I went to Derbyshire. We visited

a few small caves and went down a few mineshafts, but I always had the

impression that I was on a social outing. Yorkshire, on the other

hand, was quite different. After the first day I was always aching

all over. Living in the south I was not brought up to climb ladders

all day or carry so much rope ladder around inside pots. The weather

never seemed to be very kind to us and my old Home Guard uniform (pictured

left) and old sweaters used to soak up enormous quantities of water which

I had to carry around with me and up and down wet pitches. After

one hard day, it seemed I was expected to do the same again next day.

I was always pleased when the weekend was over but the strange thing about

caving is that, in retrospect, I always realized that I had enjoyed the

experience.

The Chairman of the SWCC was now Dr. Edward Aslett (pictured right).

He was an eminent specialist in lung diseases and had spent many years

in South Wales in connection with the coalminers’ endemic lung disease,

pneumoconiosis. There are numerous stories of his absent-mindedness.

On one occasion he took a young lady out to dinner; after the dinner

went out to fetch his car but forgot he was out with a young lady and

drove home! He was in the pub one night and one of the locals asked

someone who he was. He was told that Edward was a very famous venereologist.

The local looked at him in wonder and said “Duw, there’s Culture

for you.”.

If one was in Ogof Ffynnon Ddu and kept finding things like a pencil

or a glasses case, it meant that Brigadier Aubrey Glennie was somewhere

around. He spent many hours in the cave studying the layout of the

passages and the different limestone beds these were in. He wrote

a number of very interesting articles in the Cave Research Group’s

publications on the formation of the cave. He once asked me to help

him enter a small chamber he had found; “A screwdriver will

be enough” he assured me. I happened to be carrying a crowbar

at the time and, after about two hours hard work, I managed to make the

hole big enough to enter. Glennie was one of the leading lights

who formed the Cave Research Group in about 1947 (which later became BCRA).

His niece, Mary Hazelton, was very interested in the underground fauna

and was recorder for the CRG on this subject for a number of years.

Aubrey Glennie was subsequently president of SWCC (from 1962-68).

Now that the club had a cottage in the area (Penbont) we were getting

numerous visits from other clubs. This meant that we were quite

often asked to show them round the local caves. On one occasion,

Les Hawes and I were taking a party from the Bradford Pothole Club round

Ogof Ffynnon Ddu. The stream was pretty high, more than a foot above

the step, which is generaly regarded as the limit. The visiting

party found this a very wet and strenuous trip. Being locals and

knowing the stream well, we had no difficulty. Anyway, some time

later, Les was in Yorkshire and the Bradford club were having their annual

meet at Gaping Gill with the winch. Les was strapped into the seat

and, just as he was going down, he was recognised by one of the party

we had taken into Ogof Ffynnon Ddu. They told him they were going

to try and beat the record for the descent into the main chamber.

I believe they managed 17 seconds!

Edited by Jem Rowland, back

to the top

March 2009

|