Some Family History 1820 - 1923

by Peter I. W. Harvey contents

I was born in India, as was my mother and her father before her; his

father, my great grandfather, who was described as trader, spent most

of his life in India before him. He was Harry Wilkins Branson and

in 1832 he married Eliza Caroline Wilson Wellington Reddy.

From her surname, she is thought to have been a Parsee, a group in India

of Persian extraction. Anyway, one of the witnesses at the wedding

was a Mr. George Wellington, so she was probably related to him as well.

Over the next thirty eight years they had sixteen children. At least

one of these died while very young. They were living on the East

side of India in and near Madras. There were also other Bransons

living nearby and their names also appeared at the christenings.

Most of these children must have eventually returned to Britain but my

grandfather, Frederick George Reddy, spent his life as a solicitor in

Madras. He returned to Britain at least once when he aquired his

first wife, a Miss Girdlestone. They had one daughter.

My

grandmother, Grace Mary Jones, was the daughter of an iron trader in Middlesborough.

She obtained a diploma in mathematics at Cardiff University, not a degree

you understand [women were not eligible to obtain degrees at that time]

and trained to be a teacher, whereupon she got a job in Madras!

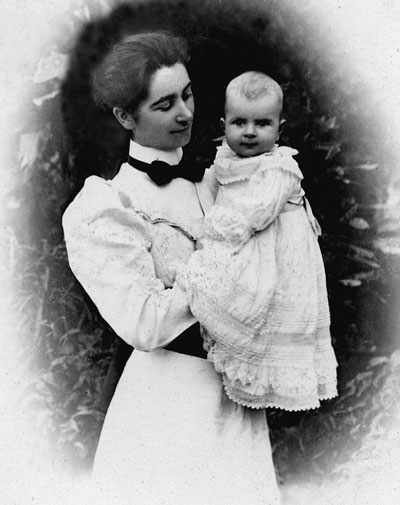

She was not out there long before she became the second wife of George

Branson and, after a while, my mother was born. It was about 1900

that George died and my grandmother returned with my mother to Britain.

She soon became involved in the suffragette movement. Her big moment

came when she chained herself to the railings outside Dewar’s Whisky,

threw a brick through their window and made a speech to the crowd that

gathered. She spent some time in prison and had food pumped into

her when she went on hunger strike. Her late husband’s brother

Arthur Branson, a judge, was not very amused. My mother, who at

the time was incarcerated at Roedean, a girls boarding school, had

a bit of a rough time as a result; protesters, even those doing it for

women’s rights, were not regarded with any respect. My

grandmother, Grace Mary Jones, was the daughter of an iron trader in Middlesborough.

She obtained a diploma in mathematics at Cardiff University, not a degree

you understand [women were not eligible to obtain degrees at that time]

and trained to be a teacher, whereupon she got a job in Madras!

She was not out there long before she became the second wife of George

Branson and, after a while, my mother was born. It was about 1900

that George died and my grandmother returned with my mother to Britain.

She soon became involved in the suffragette movement. Her big moment

came when she chained herself to the railings outside Dewar’s Whisky,

threw a brick through their window and made a speech to the crowd that

gathered. She spent some time in prison and had food pumped into

her when she went on hunger strike. Her late husband’s brother

Arthur Branson, a judge, was not very amused. My mother, who at

the time was incarcerated at Roedean, a girls boarding school, had

a bit of a rough time as a result; protesters, even those doing it for

women’s rights, were not regarded with any respect.

When the First World War started, they were all thrown out of prison.

As my grandmother had, in all but name, a degree in maths, she was sent

to the aeroplane manufacturer Avro as a welder, where she spent the war.

She was quite a strong woman; there was a meeting of the workforce to

decide on a strike and she got up and proposed they went back to work

and they all did. Meanwhile, my mother was what is known as ‘finished

off’ by being sent to a convent in France. I understand she

was supposed, among other things to learn a bit of French. I had

an experience of her French later on in France: when she asked the waiter

where the toilet was he brought her three glasses of milk.

My father and mother were married soon after the war. I never found

out much about my father’s family except that one of my names is

Warren and I understood that my father's mother was part of a family connected

with the Warren Bank, which was long ago taken over by one of the bigger

banks. My father had spent the war with the Dorset Regiment fighting

in France, a subject he did not talk about. Anyway, after the war

he transferred to the 6th Gurkha Rifles in India and it was there on the

North West Frontier, at a post called Dunga Gali, that I was born in 1921.

I had decided that the most dignified way to arrive in this world was

feet first. Apparently the military doctor did not have a

lot of experience in welcoming children into this world and, because of

my position, he was seen walking up and down muttering “what shall

I do”. Happily, the Indian ‘aeyer’ did know, and

rubbed me round the proper way. The first that my father knew of

my arrival was from outside, when a Gurkha sergeant marched in and said

“Sir, you have a son!”. One can imagine half the company

sitting on the lawn outside the bedroom watching events. I suppose

having a son was quite important in their eyes. One of my father’s

fellow officers was a captain Bill Slim. My mother told me that

he bounced me on his knee. She also told me that he and my father

both fell off their horses on some special parade - I always thought that

Gurkha officers walked with their men.

Even in those far off days after the first world war, the government

was making cuts and the armed forces, including the Indian Army, were

not immune. So it was that, soon after I arrived, my father was

made redundant and returned home to Britain. I think with a new

wife and son he was glad to come home. Slim stayed on, and progressed

to considerably greater responsibilities.

Edited by Jem Rowland, back

to the top

March 2009

|